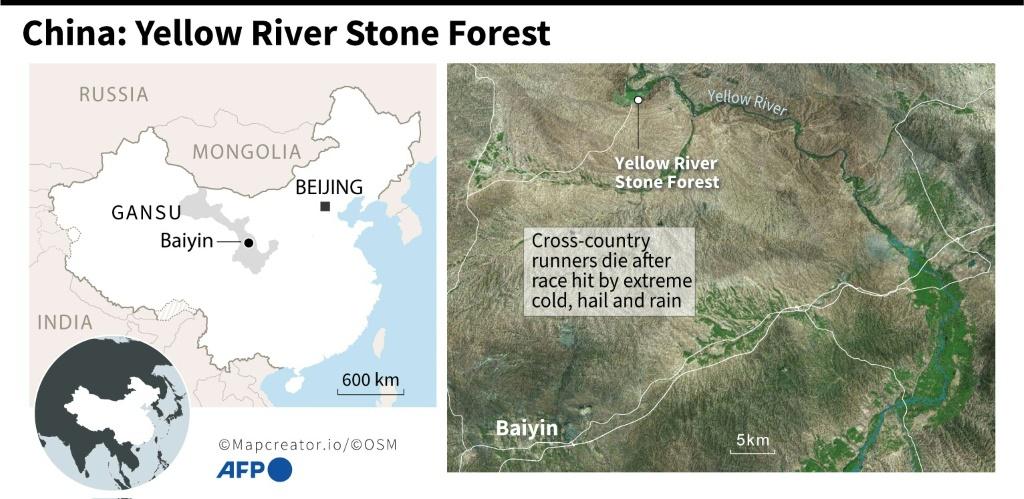

At 0900 on Saturday 22 May 2021 (yesterday), 172 participants embarked on a 100-kilometre (62-mile) cross-country ultra-marathon race in Yellow River stone forest, known as the Huanghe Shilin Mountain Marathon, in Gangsu province (China). The route was to take participants through canyons and hills on an arid plateau at elevations of over 1,000 metres (3,300 feet).

Photos and video clips posted to social media show the race kicking off under overcast conditions with participants wearing shorts and t-shirts. Several hours after the event started, extreme weather descended upon a high-altitude section of the route, with some reports citing a low of 6 degrees Celsius (43 degrees Fahrenheit) excluding wind

chill. In addition to the plummeting temperature, participants were met with freezing rain, hail and gale force winds.

A “significant” decrease in temperature had been forecast in Gangsu over the weekend, and many have turned to officials for answers as to their risk management and contingency planning. As temperatures continue to drop, many runners started reporting symptoms of hypothermia and others went missing.

A massive rescue effort was initiated, with over 1,200 rescuers dispatched, assisted by thermal-imaging drones, radar detectors and demolition equipment, according to state media. A landslide following the severe weather also hampered the rescue work, according to officials.

Of the 172 participants, 21 runners have died, and a further eight have been hospitalized in what is most undoubtedly the most significant tragedy to strike the sport since its inception. What was to be an amazing and inspirational experience has ended in tragedy.

Given that we’re in the business of Wilderness Medicine and many of our students volunteer or work on such events, we thought this a good opportunity to discuss the medicine involved.

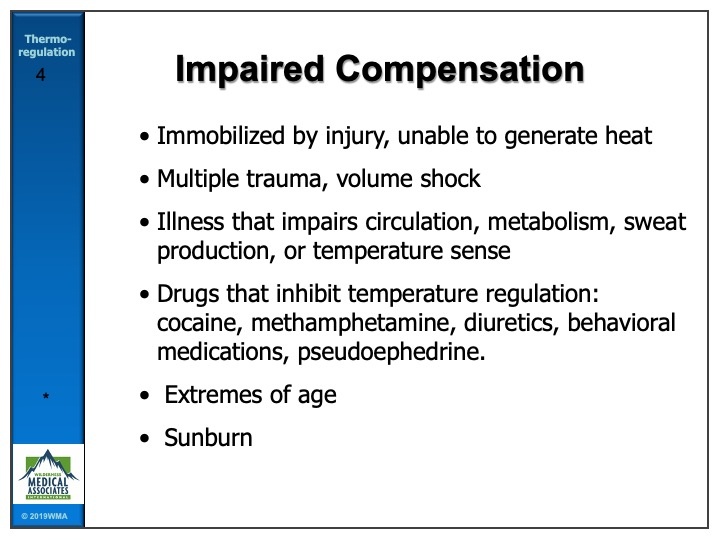

The primary concern is thermoregulation – or more simply put – the body’s ability to maintain a core body temperature that is within normal limits. Winter and low temperature environments are a very real hazard to people engaged in outdoor activities, bringing the risk of hypothermia. That said, it’s worthy of note that the risk of hypothermia is not restricted to cold environments. Any situation that causes the body to radiate heat for prolonged periods or impairs the body’s ability to thermoregulate (think large body surface area burns) brings an increased risk of hypothermia. Couple this with the fact that most elite athletes have little in the way of body fat and the fact that their pastime consumes significant quantities of energy and fluid, and the risks are only exacerbated.

Although weather patterns such as the ones witnessed in Gangsu over the last 48-hours are more typical of winter, erratic weather can occur at any time of year, but are even more common in high-altitude environments. Hikers or runners not fully prepared for the full gamut of weather possibilities when setting off in such conditions are especially vulnerable.

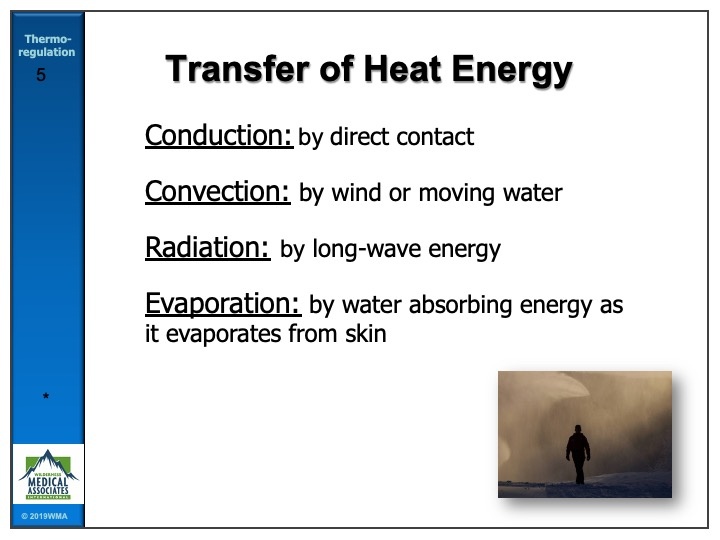

The convective effect of strong wind on wet clothes will increase the amount of heat lost from the body. Swimmers, divers, triathletes or anyone participating in water sports will also be aware that the thermal conductivity of water is much higher than that of air. Therefore, during cold water immersion, the body loses more heat than it would were it exposed to the same temperature air.

It should also be noted that the entire process from mild exposure to severe hypothermia may take a few hours – or in some cases less. Many people are surprised when told that medical issues relating to heat loss can also occur in warm environments. This is a key reason that it’s incredibly important to be prepared when operating in harsh environments regardless of the season or forecast weather.

Whilst many medical systems classify hypothermia into four categories or five stages, WMA’s curriculum talks about two: mild hypothermia and severe hypothermia. The finer distinctions serve no practical purpose in the field. For simplicity, we classify mild hypothermia as a core body temperature between 35 and 32 degrees Celsius, and severe hypothermia below 32 degrees Celsius.

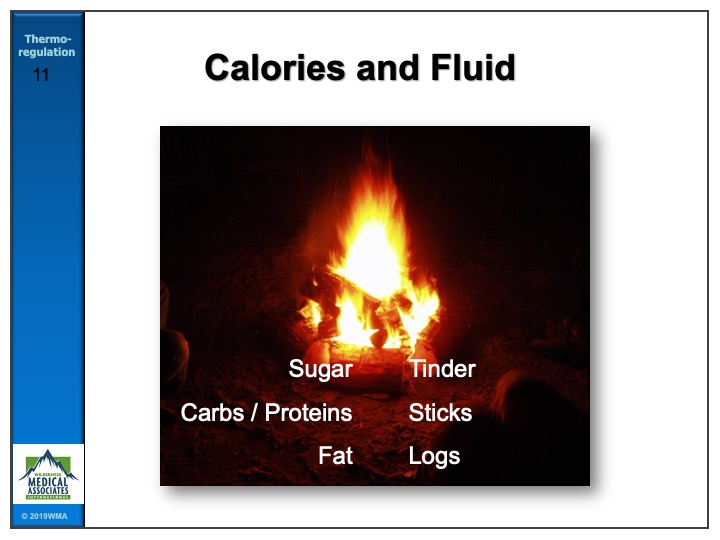

The temperature of the human body is a reflection of the balance between heat gain and heat dissipation, which introduces the topic of metabolism. Cellular metabolism underlies both thermoregulation and our respiration rate. We eat a diet of macronutrients (lipids, proteins and carbohydrates), which through a series of metabolic reactions become fuel that the human body can use for a number of purposes. In wilderness medicine, we are constantly talking about maintaining caloric intake to ensure the availability of adequate fuel for the body. Heat energy can be transferred through radiation, convection, conduction or evaporation. Metabolism generates heat. The effects of these four modes of heat transfer plus metabolism lead to a net gain, net loss or homeostasis of core body temperature.

Whilst it’s true that larger muscle masses generate more heat, your level of insulation from the elements also has a direct effect on the rate at which you lose heat. This can include natural insulation (people with greater levels of body fat content), or artificial insulation (appropriate choices of protective clothing). Endurance athletes generally have little body fat, which means that their ability to resist freezing is relatively inferior to those with greater natural insulation. Direct exposure to wind whilst wet will also accelerate your heat loss.

As we previously mentioned, we break hypothermia into one of two categories: mild or severe.

Mild Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when heat loss exceeds heat gain, and the onset can either be acute or subacute. Acute means sudden onset, for example falling into frigid waters. Subacute is a slower process and generally sets in over hours and days as a result of poor self-care, inappropriate clothing choices and/or inadequate caloric intake.

For field purposes understanding the difference between acute and subacute is important. In subacute, our patient is generally calorie depleted and in addition to warming and insulating, we need to restart the metabolic fire.

The most obvious and immediate symptom of being too cold is that you will start to shiver. This is the body trying to compensate for your condition and generate heat through muscle movement. This in turn consumes sugar, producing heat as a waste product of the burnt calories. This shivering in early stages can be overcome with will power, and in of itself does not represent the onset of hypothermia, but by no means should it be ignored. This is the point at which to stop and get help, and to rewarm. As in all things, prevention is better than cure.

Generally, we consider someone to be mildly hypothermic when they experience an altered mental status; this could manifest as lethargy, confusion or inappropriate decision making. Clinical studies have shown that as many as 50% of hypothermia related deaths have contributing factors related to inappropriate decision making.

Early onset symptoms may include slurred or impaired speech and a decline in coordination. When running in cold, wet and windy conditions, pay attention to how your partner speaks and how you run. It’s perfectly feasible that one member of a group may develop hypothermia whilst the rest do not – at least not yet. Everyone responds differently to environmental conditions, and some people are simply more susceptible than others to the effects of hypothermia.

When shivering can no longer be controlled, the patient will usually look pale and the lips, outer ears or fingers may turn blue.

The thing with sub-acute onset hypothermia is that ideally you would have recognized the signs and symptoms of cold challenge before hypothermia set in, and adopted warmer clothes, made sure you were dry and insulated from the elements, and consumed some calories. If you missed the signs and symptoms and do find yourself in this situation, it is incredibly important to stop what you are doing and treat the symptoms now, to prevent deterioration into severe hypothermia. Mild hypothermia is field-fixable. Severe hypothermia is not.

At this point the treatment is very similar to what we described for cold challenge: consume calories (mainly simple sugar), insulate from the wind and elements, keep dry, wear warmer clothes… in other words do everything reasonably within your power to prevent heat loss, and replace heat – except exercise.

Severe Hypothermia

When severe hypothermia sets in we will see a drop on level of consciousness to V, P or U on AVPU. This may be preceded by visual or auditory hallucinations. Patients who are severely hypothermic may no longer shiver.

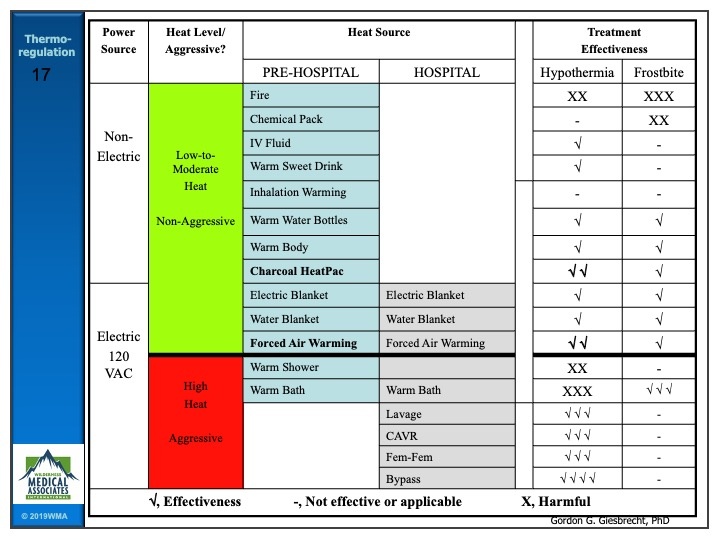

Conversely to mild hypothermia, we cannot effectively treat severe hypothermia in the field. For the best chance of survival, this patient needs to be rewarmed in a hospital and the best that we can do is package the patient with an additional heat source such as charcoal pads, insulate them as fully as possible for the environment and effect a gentle but urgent evacuation, maintaining the patient in a horizontal position. Following the ideal to real principle, if evacuation is simply not possible, the choice is taken away from you. A severely hypothermic patient may experience cardiac irritability and be susceptible to develop ventricular fibrillation as a result of inadequate care in handling. In the case of no palpable pulse, evacuation should be prioritized over chest compression. If available, consider advanced therapies such as PPV with heated and humidified O2 @ 6L/min and a warmed IV, once again on the proviso that this does not delay evacuation.

Risk factors for hypothermia

The risk factors for hypothermia in runners include:

- Temperature. This may be the most obvious of all factors, but it may also be one of the most deceptive. Hypothermia may occur at temperatures around 10 degrees Celsius, or even at higher temperatures if other environmental conditions are bad.

- Moisture. Humidity, snow, sleet or rain. Whilst most people think of continuous heavy rain. I also think continuous or sporadic drizzle, over a long time, in other activities like backpacking. Not due to physics, but psychology. People don’t put on their raincoat in a drizzle, as it’s too mild of rain and the raincoat is buried in their pack and they’re hiking and staying warm. Then they stop for lunch. And get colder. And it progresses from there.

- Conduction. When the water evaporates from the skin, it cools your body. If your clothes are soaked in water and sweat, their ability to provide thermal insulation will be significantly reduced. In this regard, cotton is particularly poor. Technical fabrics, whilst more expensive, are optimal.

- Wind speed. With stronger wind, effect of evaporative cooling will be increased, resulting in greater heat loss. If you are also wet, this effect will be multiplied.

- Physical exertion. The level of exertion expended to run a marathon (or greater distance) will leave runners hypoglycemic and dehydrated. Many participants in sports such as ultramarathon will consume gels or blocks of concentrated sugar in an attempt to maintain blood sugar levels, and most will be vigilant with their hydration regimen. That said, the demands placed on the body by an undertaking like an ultramarathon are extreme and even the fittest of athletes will have their limits. Both hypoglycemia and dehydration exacerbate the symptoms of hypothermia.

Summary

This has been a brief summary of the medicine as it relates to hypothermia in sports such as ultramarathon, but as they say prevention is better than cure.

In respect of those that have lost their lives or their loved ones, I don’t wish to explore the question of whether this was an avoidable tragedy, or what could have been done differently at this time. Investigations by competent authorities will no doubt follow and the reaction to those findings may change the face of the sport, or even the outdoor industry in China, in a similar ways to the Lyme Bay incident in the UK.

As most who partake in the sport are adventurous at heart and passionate for what they do, no doubt they will continue. For those involved in activities like this, here are a few tips to help keep you safe.

- Be prepared. Check weather forecasts, understand local weather patterns and seasonal weather behaviour.

- Respond to cold response early. Stay dry, clean and as insulated as possible from the environment.

- Invest in good quality clothing suitable for the environment and use it judiciously.

- Stay well hydrated and well fed.

- Have an emergency plan, and don’t be afraid to activate it.

- Most importantly, if you recognise the symptoms of mild hypothermia, take it seriously and prevent it from becoming severe hypothermia.

For those involved in organising events like this, the question on your mind must be something along the lines of “How can we ensure that something like this never happens again, or at least doesn’t happen on our event?”

This introduces the concept of risk management for outdoor programmes. Short of keeping you here for another several thousand words I don’t have an easy answer. Risk management for outdoor programmes is a complex animal, and one that people dedicate their careers to studying.

People often consider risk to be a simple function of probability. “What are the chances?”

This linear model is predicated on the assumption that there is a single cause to incidents, which if eliminated, could prevent accidents from occurring. In the 1970’s, a common approach to safety was the idea of controlling human behaviour through rule books and policies, leading to exhaustive manuals detailing extensive rules that must be followed. However, we soon learned people don’t always follow the rules. And rules can’t cover all possible situations, so there are times where it’s important to allow people to use their good judgement, rather than expecting them to follow rigid rules. This was the birth of “integrated safety culture,” which sought to balance the right amount of rules with giving permission for people to make their own decisions. Using judgement was seen as particularly important in places where the environment might change quickly, and the consequences of mistakes could be grave. This sounds particularly relevant to ultramarathon.

Finally, in more or less the 1990’s, safety thinkers continued to build on the work of those who had come before and brought the idea of complex systems theory to risk management. Here we understand environments such as airplane travel or an outdoor program as a complex sociotechnical system. We recognize that in the complex system of an outdoor program, there are many variables at play, and we may not understand or control all of them, or be able to anticipate where the next system component failure may occur.

The above concepts are borrowed from our friends at Viristar, who have developed a four-week, online course in Risk Management for Outdoor Programs. The course introduces the concept of risk domains – the areas in which risk reside, and risk management instruments – the tools available to us to reduce risk and teaches how to apply successful risk management strategies to adventure programs, experiential education, wilderness expeditions, and outdoor trips.

More information on our wilderness medicine courses can be found here.

If you’d like to learn more about Viristar’s risk management offerings, visit them here.

Fact Checked by Dr Peter Natarajan